Expert insight

Think differently about global diversification

January 22, 2025

Chasing performance and the fear of missing out can be psychological barriers to keeping a balanced and diversified portfolio. But investors must accept a universal truth: There will always be an asset class, sector, or security that will outperform your portfolio. Two simple thought experiments illustrate the folly of chasing outperformance at the cost of diversification.

Where does overweighting end?

First, imagine the equity investor who prudently stayed globally diversified over the years: They may understandably feel buyer’s remorse. After all, a $100 investment in U.S. stocks 10 years ago would have grown to $334 by the end of 2024 (an annualized 13% return)—more than twice the final balance of $160 (an annualized 5% return) for a similar investment in non-U.S. stocks.1 The wide performance gap between the two has many U.S.-based investors questioning the benefits of global portfolio diversification.

But with that logic in mind, why stop with global diversification? The same argument could apply to all levels of portfolio diversification. Looking at market results over the 10 years ended December 31, 2024, why bother with broadly diversified U.S. equity exposure when U.S. growth stocks outperformed the broad U.S. market by 1.4 times ($470 versus $334)? Why invest in value stocks at all?

Or given that the information technology sector, in turn, outperformed growth stocks by 1.4 times, why not just concentrate the entire equity portfolio in that sector? And why not further weed out the underperforming parts of the sector? The Magnificent Seven outperformed the IT sector by 6.8 times.2 And one stock, Nvidia, outperformed the collective return of the Magnificent Seven by 6.3 times.

You can always find an asset that will outperform your portfolio

Notes: Charts show the final balance of a hypothetical $100 investment in the relevant MSCI indexes and in individual stocks for the 10 years ended December 31, 2024. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Index performance is not representative of any particular investment, as you cannot invest directly in an index.

Sources: Vanguard calculations, based on MSCI indexes and historical stock data from Bloomberg.

Taking the past-performance argument to its logical conclusion reveals the argument’s fallacy: You end up with a one-stock portfolio. Instead of Nvidia, what if the investor had concentrated in a high-flying stock that ultimately crashed and perished?

Hedging the unknowable

That one country or region outperforms the others is not a failure of global diversification—on the contrary. Back in 2015, nobody knew for certain which region would do better. The only certainty was that the gains in the part of the market that outperformed could offset the losses in the other parts of the market. And that is exactly what happened over the last 10 years.

An investor with a portfolio diversified across U.S. and non-U.S. stocks in a 60%/40% ratio would have had returns close to 10% annualized over the past 10 years—respectable returns delivered with considerably less risk than the uncertainty of choosing between an all-U.S. portfolio and an all-non-U.S. portfolio.

To understand how diversification works, let’s play our second hypothetical game. Suppose you have an investment with 50/50 odds of two possible outcomes: a high return (say 13% annualized, similar to the all-U.S. stock portfolio over the last 10 years) and a lower return (say 5% annualized, similar to the non-U.S. stock portfolio). Notice that this is not a bad investment, as even in the worst-case scenario, your return is at least 5%. Moreover, given the 50/50 odds, the expected value of this investment is actually 9% (a 50% chance of a 5% return plus a 50% chance of a 13% return).

But what if, along with that investment, you’re offered an insurance policy—and get 9% no matter what? The insurance contract is that you get paid 4% on top of the lower return outcome, but you have to pay 4% to the insurer if you get the high return.

The insurance contract removes the risk of the 50/50 investment. Who wouldn’t take it? Of course, if the outcome is the 13% high return, some investors may regret having added the insurance. But that’s no different than complaining about paying insurance policy premiums after a year of no car accidents or property damage. After some waffling, when offered to play another round of the game, we stick with the insurance every time!

Of course, this comparison isn’t perfect. Unlike insurance, diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss. But it acts as a hedge against risk, avoiding the extremes.

Current valuations are vulnerable

Although diversification makes sense in any environment or time period, it may be particularly important now. By most measures, U.S. stocks are overvalued. While non-U.S. markets have also appreciated, Vanguard broadly considers them fairly valued.

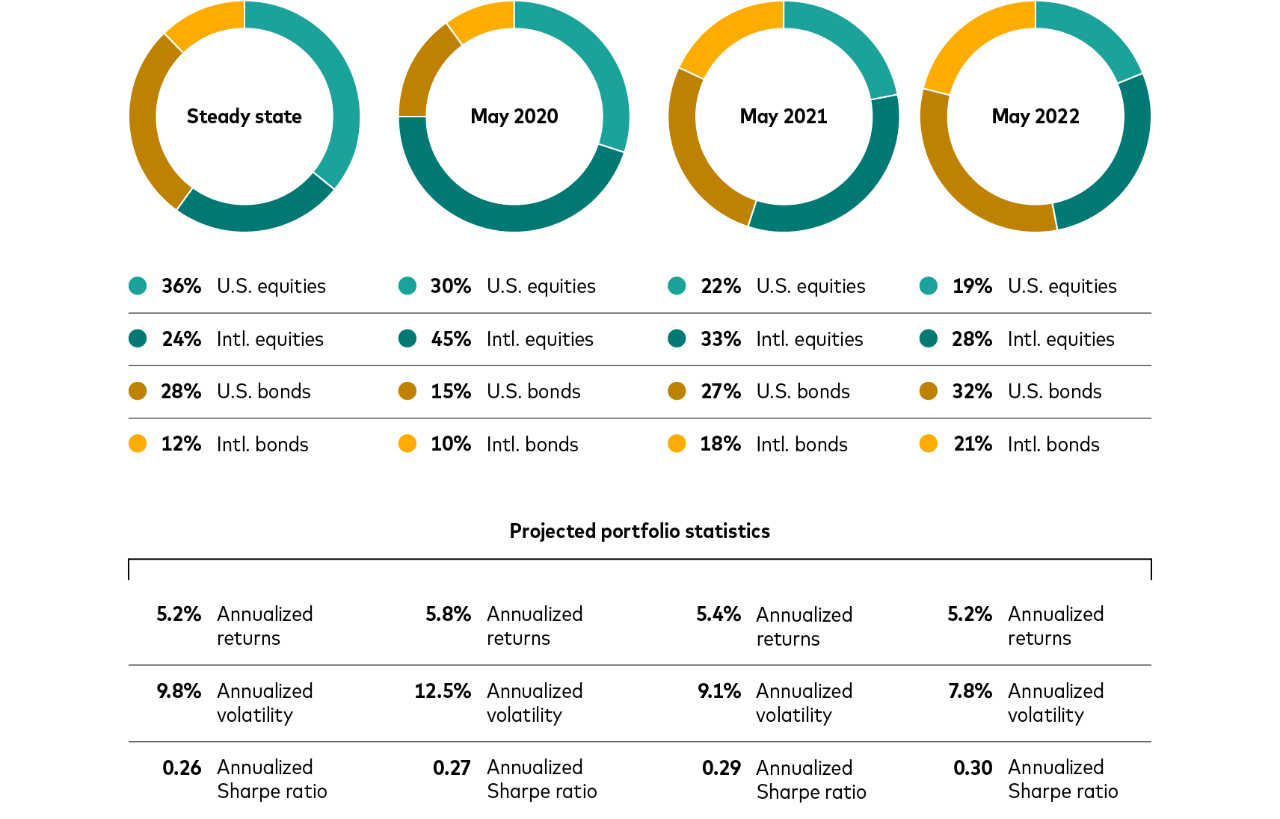

By no means do we predict an imminent market correction. No one can predict the timing or magnitude of a correction, and momentum may continue to carry the day. High valuations are not a market timing tool; instead, they are a useful signal warning us of market risks. Long-term investors would be well-served sticking with portfolio diversification—that is, rebalancing their portfolios back to the diversified mix of assets that is appropriate for their risk profile and goals.

1 Returns in all the scenarios are based on our calculations using the relevant MSCI indexes through the 10 years ended December 31, 2024.

2 The Magnificent Seven are the seven stocks that have driven much of the market's returns over the past few years: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla.

Notes: All investing is subject to risk, including the possible loss of the money you invest. There is no guarantee that any particular asset allocation or mix of funds will meet your investment objectives or provide you with a given level of income.

Investments in stocks or bonds issued by non-U.S. companies are subject to risks including country/regional risk and currency risk.

Funds that concentrate on a relatively narrow market sector face the risk of higher share-price volatility.